Also available as a PDF. Or view this on our primary site.

This essay was first published at Another World, our supporters’ journal. Supporters get early and exclusive access to essays, free downloads, free courses, and discounts on purchases.

W.McCrae:

I’ve always been prone to nostalgia, but at least I come by it honestly.

My father’s affinity for the fields of history and geography made strange alchemy with my mother’s persistently-unfulfilled religious longing. I wound up the sort of kid who cherished old washrags after learning they had been used to wipe my nose as a newborn, wracked with a feeling of listless significance wherever I happened to perceive a throughline between the world around me and my own life story in the making.

So I started out the gate primed toward a strong sense of place, to awareness where I am as much as where I belong in it. Early childhood in a small town is a series of locations played on repeat, like recurring dreams: backyards and bedrooms and schoolrooms and long rural arteries under the soft gray sky, always glimpsed from the car’s back seat. Lacking agency in where you are permitted to go, you may find yourself closely interrogating wheresoever you happen to be: the sights, the scents, the little fascinations of it. In the manner of being left to play with your mom’s coworker’s kid, you perform outreach in order to better understand your circumstantial companion, feeling out the shape of it by its irregularities—the broken corner off the vinyl countertop, the tree whose trunk bows just-so.

Here we are again.

Across many explorations, maybe only in retrospect, you may come to find that the places you inhabited were speaking back to you.

Good to see you, too.

Maybe what it means to be from a place is to lose the sense of where its story ends and yours begins.

R.G. Miga:

It’s hard to know if the animals started coming back in the past few years, or if I only just started paying attention.

I remember a black bear on the side of Route 81, south of Binghamton—dead, legs stuck out in front of it as it lay on its side, like one of its toy-store kin. A state trooper was studying it from a distance as if it were a crashed spaceship. Black bears range from Canada to Virginia, and maybe further. But something about seeing one so close to the rustbelt hub where I grew up was surreal: the natural world verging onto the industrialized riverbanks had always been tame. The forest was a scrub of second-growth trees, barely covering the modesty of hillsides that had been completely denuded in the past century; the animals were harmless little creatures—the kind you could swat away with a tennis racket, if it came down to it. And then, somehow, this lumbering giant.

Dead or not—seeing an animal big enough to swat me away felt like a turning point, in that smokestack wilderness.

North of there, in the suburban neighborhood where I now live, there are periodic flurries of emails about wild animals raiding the tree-lined enclaves of college professors and retirees. Whispers of mountain lions moving back into the state like revenants. Coyotes were said to be stalking the streets a few months ago, on the prowl for oblivious housecats. A pair of gray foxes, presumed to be rabid, were spotted not far from the elementary school that my kid attends. No reports of wolves yet; god willing, it won’t be long before they return, to run down the cosseted, citified deer who graze the landscaping and stroll along the sidewalks at all hours of the day.

The raptors are the most welcome return. After being hunted almost to extinction, bald eagles made a dramatic comeback in the Montezuma Wildlife Refuge just up the lake; a photographer who works in the crumbling factory-turned-studio down the block said that a juvenile flew right over our house. Hawks, falcons, and ospreys seem to be adapting well too. Recently, a hawk nailed a squirrel, winged it up to the branches of an ornamental maple tree, and promptly began eviscerating it—to the absolute horror of one of our neighbors who stood about twenty feet away. I almost had to stop my car before I crashed from laughing.

We’ll lose the winter, sure. That will be something to mourn. But we’ve lost so much already—jobs, infrastructure, local culture—that it’s almost worth it to see something, anything, come back to life so vibrantly and viscerally in these dying, half-ghosted towns.

W.McCrae:

When I was around seven years old, I had a dream about being a grown-up. My long adult shadow fell across the ground ahead of me as I approached my house, but when I came up to the door I was faced with the realization that my family no longer lived here. The place where I used to sleep tight and roughhouse and do my homework, the place where I had become myself, was closed to me; this house was some other child’s home now, and I couldn’t ever go back again. I had no coping mechanism to steady myself against the magnitude of the loss. I dropped to my knees and cried, and woke up with a new fear that I was too young to know what to do with.

To this day, my father still owns that house. I can always go back. But life is funny sometimes; in spite of its continuous form and function and even its tea-stained smell, at some point, that house quietly stopped being my home. As a courtesy these days, I call up my stepmom before making plans to stop by. The neighborhood where I grew up, our cozy little outpost on a stirring nurseryland sea, now has different names on half its mailboxes, as folks have passed away or moved on and new faces rushed to fill in behind them. They’re going to build another subdivision in that 20-acre wooded lot across the street, where Jerry lived for six decades and raised his kids and buried his wife. I was just getting used to the old subdivision that sprung up in 2005.

I read somewhere that this town, population under five thousand at the time of my birth, has become one of the fastest-growing in the state, Portland’s up-and-coming most-desirable bedroom community. I should be more gracious about that. It was sure a nice place to grow up; how could I begrudge other people’s children for getting to make a home of it?

Somewhere along the line, the continuity was broken. I grew distant from the place that made me; I stopped conversing with those sweet old spaces where I used to fit, just so. Either they changed or I did.

Growing up means outgrowing things, too.

R.G. Miga:

Looking at the survey maps from 1970—a scant twenty years before my parents moved into the house where I grew up—the place that would be our neighborhood is nothing but a bare hillside. The main road is there: it reaches tentatively up from the shoe-factory town at the bottom of the hill, down in the river valley, and stretches out into the farmlands and swamps that dot the Valley Heads Moraine. But the whole exurban development where I spent my childhood had yet to be built, maybe hadn’t even been planned yet. So much was done to the land in such a short time.

This isn’t nostalgia for some verdant dream of the past. That hillside had already been clear-cut and grazed for generations. It was no Eden. But it is amazing to think about how short the history of that strange place will be: conjured out of nothing by the powers of cheap credit, fossil fuels, the arcing currents of global finance; probably doomed to fall into ruin within my lifetime, now that the economic tide has ebbed.

The place makes no sense. Built a half-day’s walk from the major economic center—twelve hundred feet of elevation above the most dependable water source—it sits in defiance of twenty-five thousand years of engineering logic, a defenseless hill fort. The planners probably thought its height would make an ideal destination for flying cars in the decades to come. Future archaeologists will find the footings of our houses and wonder what befell us, to be driven so far from everything else. A leper colony? The ritual compound of some apocalyptic cult?

With the right kind of eyes—those of a frustrated, self-isolating teenager, say—you can see how deeply weird these suburbs are. Everything human happens in spite of the built environment and not because of it. Sprawling, featureless houses, designed from the inside out, with no relationship to the landscape; yards of unproductive earth given over to somebody’s fantasy of ancien régime splendor; a complete absence of communal space, except for the inhospitable rivers of asphalt that ring everything around. It’s a necropolis for human imagination. Compared to the villages back in the Old Country—settlements carefully built up over generations at a sustainable scale, beside forests and streams that never lost their names—this place is a fucking fever dream.

So much done to the land in such a short time. Now it’s falling apart. And still the green stands waiting all around.

W.McCrae:

The first steps of my young adulthood were an attempt to sprint across highway traffic, dodging-and-weaving student loan payments and the ever-mounting cost of rent along the I-5 corridor. Spooked and overwhelmed, I questioned whether the Pacific Northwest still held anything for me at all: in the span of a decade, it had seemed to become disconcertingly dry and unfamiliar, too trendy and too bustling and overall too much. I longed to retreat home, but saw nowhere to go, and so in a fit of disaffection I embarked on a years-long sojourn to New England shortly following my 23rd birthday. I was searching for something new that felt old. Somewhere secret and unspoiled, a world like how I remembered it.

In retrospect, the flip-side of West Coast economic growth and gentrification seems self-evident; but lacking maturity, I could only gain perspective through experience. On the Maine coast I saw the old ports and mill-towns, those half-crumbled hollows like eggshells on the beach; in the mountains of New Hampshire I made my living in an artificial industry which lives and dies each season at the whim of rich vacationers from Boston and Montreal. In between, I shoveled winter snow and salted ice and laced tall boots just to step outside and empty the garbage. I slogged through mud season, then chafed and swore at relentless August humidity. I skirted tall grass and crept through the woods, nervous of Lyme’s disease. One morning early on, I had to pull off the side of the road to cry out an abrupt fit of homesickness. All of a sudden, I had comprehended that the trees of the Northeast were just too small, inappropriately brown and naked in November, and grief came pouring out of me.

Of course, I found things to love about New England during my time there, but I still jumped at an excuse to return to the Northwest as soon as one was presented to me. The East was not a failed experiment, I told myself, no—it was just that my family needed me. For the first time since childhood, I entertained the hope of having a home to return to after all.

So back I went, to the ever-green and to the house where I’d grown up. Secure beneath swaddling cloud cover once again, I spent the spring of that year celebrating my own homecoming: I drank the geography of Mount Hood and the Sandy River, her valley and all her lovely in-town tributaries. I flirted with the native berries and the flairing oyster mushrooms whose gray-gold variety is uniquely our own. I wore the perfumes of cedar rot and sphagnum moss and twangy wet denim, I hiked wood and field without fear of biting insects, and I wore Birkenstocks every single damn day just because I could, because it was my birthright to go bare-toed year-round and because I was finally home.

R.G. Miga:

My dad passed away suddenly in 2022. He was only sixty-three years old. His death brought a definitive end to my childhood and severed our connection to the place where I grew up. The only reason that house on the hill was built was because of the tech company in the valley below—the company that kept my dad employed for thirty-five years, gave him a livelihood to support our family. Without him, there’s not much left. My mom will spend a few more years in the house on the hill, saying her goodbyes; after that, we’ll probably bring her north to live with us.

When my dad died, it wasn’t just losing a parent: my family lost our last link to that brief, beautiful moment of prosperity—the historical anomaly of affordable housing, cheap gas, and steady work.

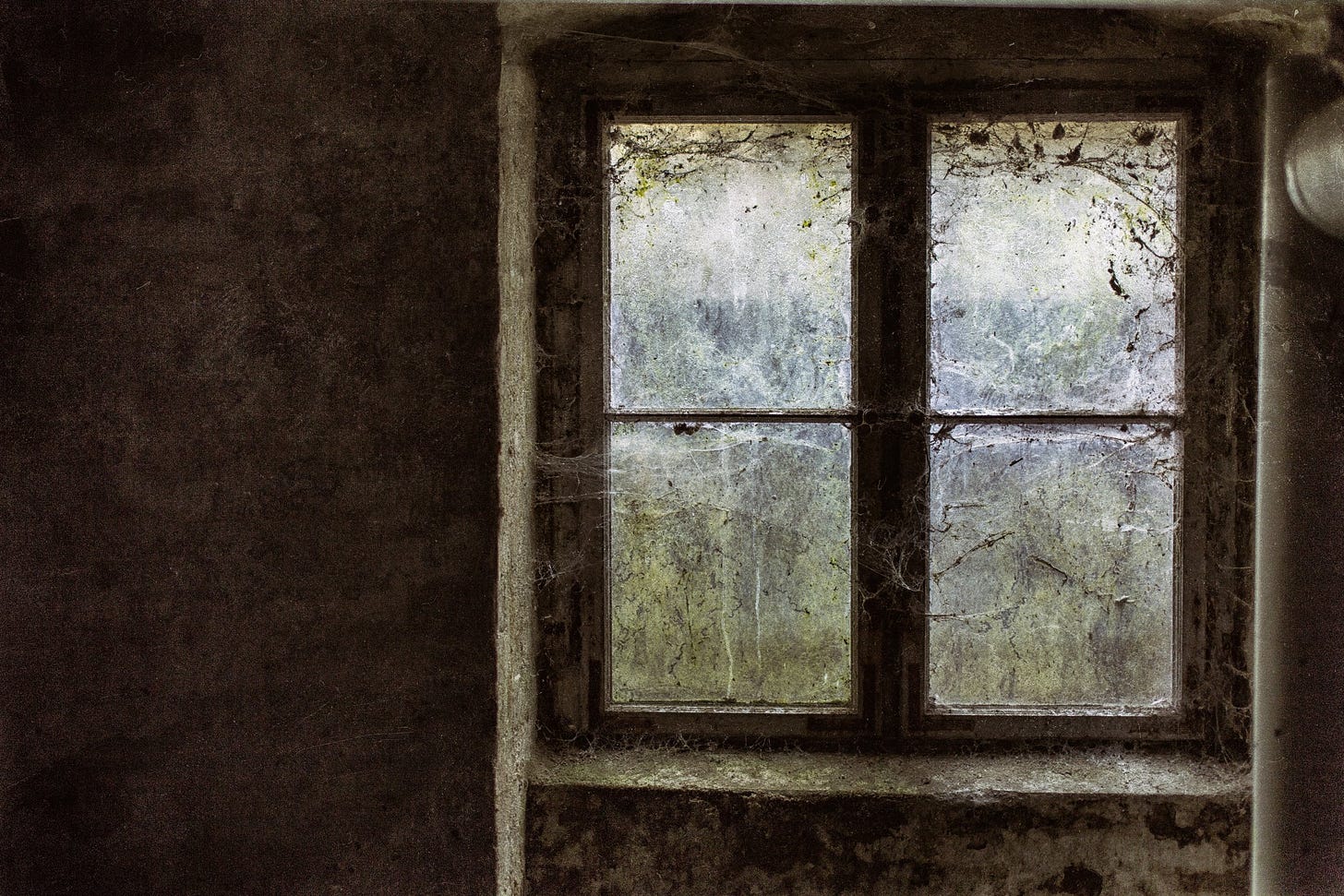

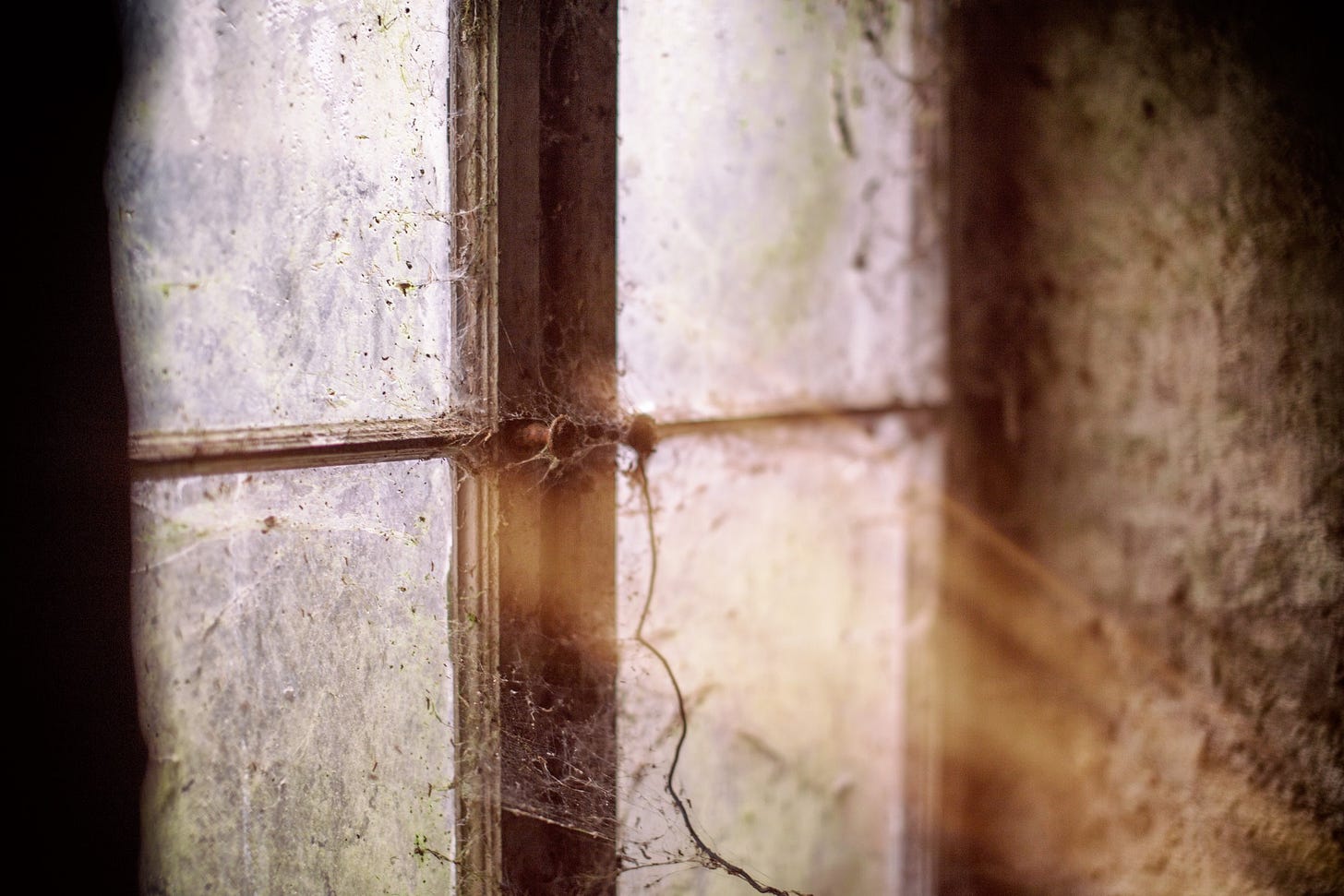

The place is used up anyway, like so many of the other towns across the Northeast. The jobs that brought people like my dad to the valley are mostly gone. The factories and the offices and the local businesses that grew up around them are shuttered and decaying. When I was young, my mom would drive us down the hill to meet my dad for lunch; the sidewalks would be teeming with people, the shops and restaurants full. It’s all empty and quiet now. Cobwebs and shadows and gathering rot. Same as it is across huge swathes of the region, this archipelago of ghost towns in a sea of green.

Driving now along the crumbling highways—Binghamton to Utica to Buffalo and back, the triangle of interstates into which my family’s whole history has somehow disappeared—the thing that haunts me the most isn’t some rattling, Gothic vision of death. Instead, it’s the specters of happiness that still linger in the ruins—not whispering one day you will be like me, but you will never be like this again. You can still trace the outlines of happier times in these places. It’s fashionable to declare archly that, well, you know, things were never that good in the past. It was all problematic. And, yeah, maybe it was built on lies and thievery too much of the time. But you know what—it was still pretty fucking good for a while there, for a lot of people. These hollowed-out places were real once. Nobody built a house in any of these towns a hundred years back and thought, “Someday—if there’s anyone left at all—this will all be a tumbledown wreck, full of aimless people who lost a vital part of themselves and can't remember what it was.” There was something worth living for here, once. That’s what haunts me.

W.McCrae:

And yet.

Nothing has really changed in the Northwest, in the sense that everything is still different. Rent is still out of control and traffic still sucks and you still can’t find any trailhead on the mountain or down the Gorge that isn’t completely overrun, seven days a week. Wintertime frays at both ends while summer gorges herself, now staging opening salvos in May, holding late October in her droughted grasp. Mid-season, you can look the sun right in the eye: the heat is stifling but the glare is baffled by smoke. Blood-red skies and parched Decembers, Himalayan blackberries and brown marmorated stink bugs—at least you can still make a killing in real estate. Inch by inch the forests and the small towns are swallowed and excreted in one long smooth suburb. It’s safer than rural living, anyway. You know, homeowners insurance doesn’t cover wildfire damage anymore.

I’m afraid that the place that made me, the place that I used to be a part of, is dying, and its corpse is every dry creek bed and its ghost is every month that begins and ends without rain, spectres choking and gasping ash, rattling chains at the bitter injustice of it all.

R.G. Miga:

And still the green stands waiting all around.

The Northeast isn’t wildfire country. If anything, the changing climate means the northward march of subtropical heat into winter’s former domain. The natural world is poised to come roaring back, supercharged and full of vengeance. I give it a few decades—assuming there are any jobs left by then—before the final holdouts in our old neighborhood get tired of beating back the relentless jungle and surrender. It’ll be the same story across the region. There is a leviathan made of wild grape, Virginia creeper, red sumac and yellow birch—swimming up from down south, along the growing currents of warm weather, getting closer. I imagine it will swamp the little raft of suburbia that some idiot dreamed into being on that hilltop, where I was lucky enough to have a home for a while.

It’s still too hard to imagine strangers living in our old house. Too much like how things used to be when my dad was alive, like somebody else stealing our happiness. Too painful. Instead, I prefer to think about what it will be like when the green reclaims its rightful place. The lawns buried under new ecosystems, drinking up the tropical rains and becoming something wilder; the hawks and foxes restoring balance to a world once ruled by housecats; the owls roosting in my old bedroom.

There’s already a lot to mourn, and more coming. But we’ve lost so much already. It’s worth imagining something coming vibrantly back to life.