A Ring Around Utopia

"The way to counter the weaponization of Utopia is not to attempt to grab onto it and hold it hostage—but to let it go."

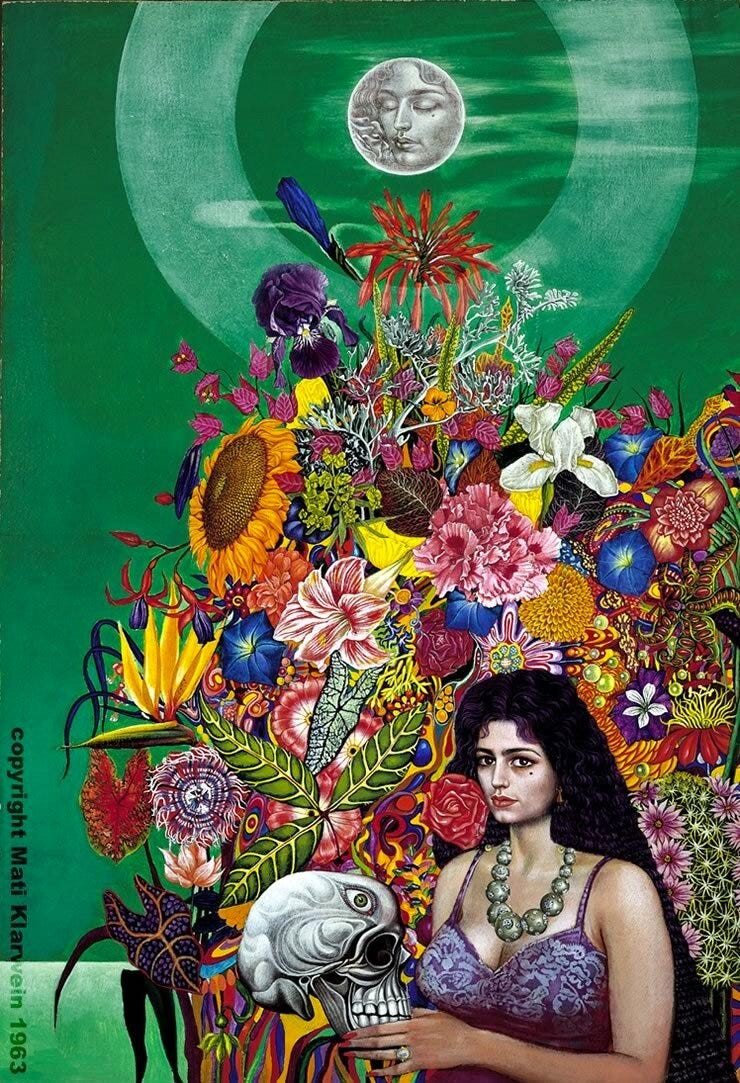

“The rose is the true revolutionary, opening toward the light, sovereign, radical, rooted in place—its own blooming, its own existence, its own just doing what a rose does—is a beacon, an instrument for the manifestation of Utopia in the here and now. A conjuring of Utopia void of coercion. The extent of its freedom—of its own volition—defined by the reaches of its thorns.”

Come, let us conjure. Let us gather and link hands. The fire has burned a while, and the brew it warms, begins to quicken, to writhe and hiss like coupling serpents. We start to chant. Clouds of steam are rising. Now grey, now dun, now the plumage of paradisal birds. We can see the very colours of the notes we are singing; they curl about the steam like fern tips, then are lost in shifting folds of evening. The chant achieves zenith and we fall silent…

We are no longer in a circle of rose bushes but upon the seashore. The fire and cauldron have disappeared. In their stead, there is a coracle. We climb inside and disembark on a voyage to expropriate a weapon of our enemy. That weapon is an island. And the island is called Utopia.

This is not quite a voyage in search of a perfect society. The name of this island, Utopia, comes from the Greek ou (οὐ) which means “not” and topos (τόπος) which means “place.” Utopia is no-place. Therefore, it is not paradise, but something closer to the locus somnium, the place of dreaming.

Similar to dreams, if Utopia is no-where it is also everywhere. It cannot be charted, only circled, slowly, by the soaring albatross. It is a similar Greek word, eutopia, which means “good place”— and its eventual conflation with the word utopia (no-place)—that has beguiled many into believing we are searching for unattainable paradise. However, Utopia is unattainable only insofar as dreams are unattainable, and only good and paradisal insofar as dreams can also be nightmarish.

The weaponization of Utopia is one of the most common means by which agents of empire and state attempt to dismiss, disqualify, quell, or silence the revolutionary aspirations of radical visionaries. It has also been used by those selfsame radicals in wars against each other that only ever seem to amount to “pyrrhic victories,” and are often waged against those that the aggressors would do well to stand beside as comrades, if not always as friends.

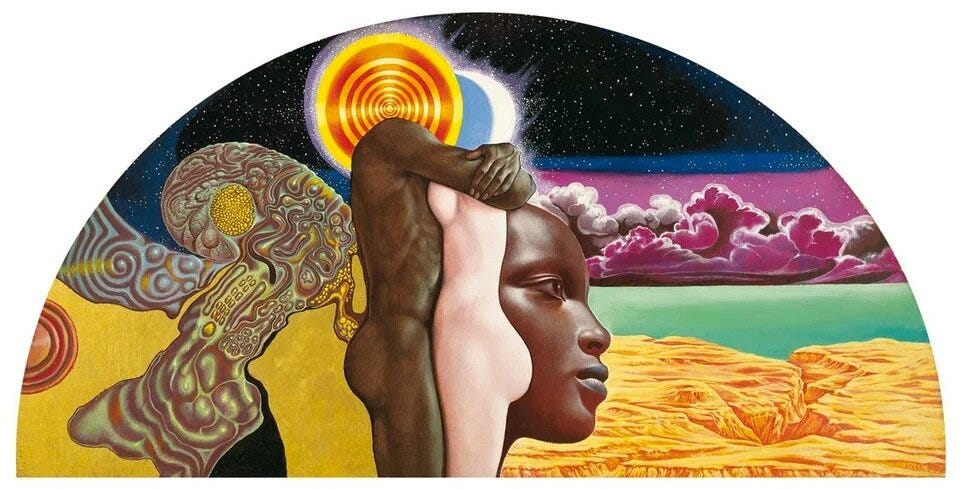

By traveling to Utopia, we may recuperate the potential for this fraught and lovely place of dreaming as an important tool in the struggle for emancipation. By traveling there, we can nullify the barbed dismissals of our enemies while at once bolster our own rhetoric. And through an understanding of immanence rather than transcendence, we can see that no-place is paradoxically every-place.

We therefore become imbued with the power to realize utopias in the here and now.

The Voyage

There is no nautical chart to reach Utopia. The routes for voyage are as varied as there are travellers, in the same way that no two people dream entirely alike. What is encountered upon arrival will also differ from one traveller to the next.

Despite its many unsavoury attributes, the novel Peter Pan aptly illustrates this point. Never Land, the name of the fantastical country that Pan inhabits, is similar to the literal meaning of Utopia: no-place. The author of Peter Pan, J. M. Barrie, once explained that a map of Never Land, if one existed, would resemble the map of a child’s mind, dreamlike, and void of boundaries.

Neverlands are found in the minds of children, and while each is always “more or less an island,” they differ from child to child. The Never Land of one child might have a “lagoon with flamingos flying over it,” while the Never Land of his brother might have “a flamingo with a lagoon flying over it.”

Furthermore, as Pan himself proclaims, the way to get to Never Land is to “take the first star on the right and head straight on till morning.” These directions, in which conventional perceptions of time and space are warped, make up a magical formula for flight, for vision. Poetic formulae such as these will aid us in reaching Utopia.

Such fabulous voyages echo the immram genre of Irish literature. Immrama are tales involving voyages over sea to mysterious islands. For example the Voyage of Máel Dúin, in which he and his companions go from island to island. Over the course of their adventure they encounter islands of horses and demons, islands of boat-eating ants, islands of birds that sing psalms, islands of fire people, islands of eternal laughter, islands of women who pelt them with nuts, islands with sky-rivers that rain salmon, islands of apples, of sleeping elixirs, of intoxicating drink, of crystal bridges, angry smiths, revolving beasts and many more.

Utopia has been widely visualized as an island for at least as long ago as Thomas More published his novel, Utopia, in 1516. More’s novel, about a fictional island in the Atlantic ocean, is responsible for the way in which the term “utopia” is used today, both in political discourse and common parlance.

Islands can be perceived as complete unto themselves. They are surrounded by water, and can thus be comprehended on their own terms. Utopia has often been approached as an island realm because the island is a microcosm, a magnet that draws the unknowable vastness of the cosmos into an intimate relationship with the curious traveller, a tiny keyhole through which a far vaster landscape that lies just beyond might finally be glimpsed.

Oscar Wilde once stated: "A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing. And when Humanity lands there, it looks out, and, seeing a better country, sets sail. Progress is the realisation of Utopias.”

Liberals and other believers in the myth of progress view the voyage to seek out Utopia in terms of linear time, and keep their eyes fixed on a horizon that disappears the closer you get to it, like approaching a rainbow from a distance.

Yet for radicals in the true sense of the term, the voyage is a memory of the future, and a premonition of the past. The term radical comes from the Latin radicalis, which is derived from the word radix, or root. Radicalis literally means “forming the root” or “inherent.” Therefore, radicals are those “at the root,” concerned with uncovering and nurturing something thought not to exist or thought to have been lost.

However, that something is always just under the surface; it is all around and never went away, despite the fact that the way to uncover it has been made ever more obscure, and in many cases, deliberately obstructed.

The Wall

There is one island upon which Máel Dúin and his companions stumble that closely resembles the hostile way the term utopia has come to be used: an island surrounded by a golden wall.

The agents of empire and state erect a wall around Utopia both in an attempt to possess it and also to prevent revolutionaries from landing there in their coracles of unfettered dreaming. These walls are justified by arms. It is not difficult to accuse an adversary of proffering utopian ideas when you are looking down the barrel of a gun.

Truly, we might go so far as to argue the most concise definition of the state is a wall erected for the purposes of governance by coercion. This wall can take many forms, and can be abstract as well as physical.

Think of the origins of the state in the city-states of Ancient Greece, of the polis. The city walls delimit the state from wild nature, and the “civilized” from the barbarians, or in other words, from those beyond the wall who the state has yet to subjugate. Civilians are governed by laws. These laws are walls in the abstract, substantiated in the physical by the force wielded by police (the word police is derived from polis, city).1

These urban laws, these laws of the city, rarely correspond to the laws of nature. The word politics itself comes from the Greek politiká, which literally means “the affairs of the city.” When city-states forcibly expand the circumference of their walls and subjugate ever more people and lands, they form empires. Therefore, the wall is a fundamental characteristic of both the state and of imperialism.

Radicals would do well to remember the connection between walls and the state before heatedly dismissing a rival as “utopian,” for the dismissal of something as “utopian” is to erect a wall and enforce an enclosure upon the fields of the Possible.

A paradox emerges here. The way to counter the weaponization of Utopia and the accusation of employing “utopian rhetoric” aimed at radicals is not to attempt to grab onto Utopia and hold it hostage—but to let it go.

No one can grasp what cannot be grasped, and as we have seen, the landscape of Utopia and the ways of arriving there are idiosyncratic to each person. Utopia for one might be torment for another.

When we realize this, we might cease to engage in pyrrhic wars, in the dogmatic enshrinement and subsequent ossification of political theories, and the zealous reduction of political vision to existential identity.

Thereby we might overcome one of the greatest pitfalls of the radical left. To impose one’s own vision for utopia on another, or to coerce another into believing there is only one true utopia, one true anarchism, one proper modus operandi for implementing revolution, is not only a twisted perversion of life force, it will always fail.

The Ecotone

In the natural world, the world beyond the polis, there are no walls. Instead, there are ecotones. Ecotones are those edge spaces that emerge where two or more ecosystems meet. They are not the product of separation, rather, they are the product of intimacy and arise as points of encounter.

Beaches, the shores of rivers and lakes, deltas, the edges of forests, the spaces between mountain and valley, between grassland and desert, between tundra and boreal forest, are all examples of ecotones. In the ecotone, there are no hard boundaries, no neat demarcations of self and other so characteristic of the logic underpinning the nation-state and indeed, the modern world.2

Instead, in ecotones, one ecosystem blends seamlessly into the next. This blurring of identities, this blurring of boundaries, gives rise to a very rich variety of species: ecotones are home to the highest amount of biodiversity in the natural world.

There are two reasons why attempts to improve society driven by utopian visions fail. One, as we have already discussed, is when utopias are imposed on others by coercion. The other is when utopias are established based on the perception that they are separate from, or superior to Nature, to the more-than-human world.

In Thomas More’s novel, the island of Utopia is inhabited by sun-worshippers, moon-worshippers, planet-worshippers, ancestor-worshippers, as well as monotheists, who all co-exist and respect each other. Curiously, atheists are a group that are mistrusted and frowned upon, yet begrudgingly tolerated. The reason being that if atheists are not motivated by rewards or punishments in the afterlife, they will inevitably be given to lapses in morality.

For revolutionaries who behold a vision of immanence rather than transcendence, it is not necessarily atheism that ruptures harmony or causes lapses in morality, but a failure to recognize that our ability to not only survive, but to thrive, directly depends on the health of Nature. We may recognize all Nature imbued with spirit, we might recognize the interconnection of all life, or both. As some kabbalists have hinted, it was not mankind that was expelled from the Garden of Eden by God. Rather, we still reside here. Truly, it was God who was expelled from the Garden by mankind. We are surrounded by miracles, despite some being unwilling to see them.

Friedensreich Hundertwasser was a painter and architect that applied some of these observations to his designs. Hundertwasser was a committed opponent of the straight line. To him, straight lines were “godless” and “amoral.” He is known for his undulating lines, bright colours, and use of live materials in buildings. According to his design principles, not even floors should be flat. He wrote: "An uneven and animated floor is the recovery of man’s mental equilibrium, of the dignity of man which has been violated in our levelling, unnatural and hostile urban grid system. The uneven floor becomes a symphony, a melody for the feet and brings back natural vibrations to man.”

Hundertwasser’s buildings break through the rigid right-angled walls erected around the realm of the Possible, and show what a society could look like, how what it means to live in a “city” could be reimagined.3

Hundertwasser believed in what he called “window rights.” This is the right that each person living in apartments has to paint and adorn an arm’s length radius around their own window pane. The individual thereby is free to express themselves and exercise their creative vision anyway they like, whether by having fruit trees growing through windows, plants growing from the walls, patterns, textures, adobe facades embedded with shards of coloured sea-glass, and so on, and all painted in accordance with the unique geometries of their own inspiration.

In so doing, one’s personal freedom is simultaneously enshrined, highlighted, and guaranteed by the neighbours one window over. What to some may appear at first as an incoherent design, as an anarchic artistic free-for-all, is ultimately revealed to be a building whose beauty is defined by the interplay between each individual piece, the complimentary hues and contrasts in tones and textures, variations in decor, which make each unto each shine all the more brilliantly upon the backdrop of the rest.

The Rose

Consider what these observations can mean in relation to radical political philosophy. If the inspiration for our utopian visions emerges from the glowing root of immanence, rather than transcendence, we can cease to wait for utopia to manifest in the “after life” or in some world to come after the revolution—when capitalism and the state are no longer—but recognize it unfolding around us and fulfill our own part in fomenting that revelation. This does not imply a call for apathy or for complacent acceptance of destitute material conditions, but the opposite. Immanent Utopia can help us break through inertia, ennui and despair, and thereby rend the illusion of impotence.

Instead of the tenets of ossified political theories—political theories guarded by gate-keepers who profit off of their role in the controlled curation of dogma—our actions can be guided by deeply considered ethics, strong enough to never be compromised yet supple enough to deal with case specific situations.

The resurgence of imperialism, the inception of colonialism, the birth of industrial civilization all coincide with the dawn of the modern world. Common land became enclosed, territories fell under dominion of one empire or other, and, eventually, people became divided and parcelled off into neatly defined nation-states.

At the same time, imperial compartmentalization occurred in the realm of knowledge. We find magic being separated from science, philology being used to justify the myths and identities of nation-states, the devaluation and exclusion of art in relation to “scientific” pursuit, and a host of other demarcations. This was not the case in the medieval period.4

To approach knowledge from the perspective of the “wall” rather than that of the “ecotone” is partially responsible for the destruction of the natural world, the subjugation and erasure of culture and language, and the dispossession of people from the necessary resources and means to sustain themselves and flourish in perpetuity. A select group of people styling themselves as the guardians of marxist or anarchist philosophy, for example, is a perpetuation of this selfsame process.

Knowing that there is no one true utopia—and that coercion is inimical to the realization of any utopia—can lead to a broader understanding of anarchism. The defining characteristic of anarchism is revealed to be its uncompromising opposition to coercion, and not simply to “hierarchy” as many believe to be the case. Anarchism is a politics of volition, and relationships that appear to be “hierarchical” are sometimes entered into voluntarily, as exemplified by many pre-industrial and indigenous cultures and communities.5

Volition can stretch far into the sky, reaching toward the light like the branches of a tree, with its only limit being that which is established by the branches of the trees that surround it and with whom it interacts, as well as the health of the earth, sunlight, and water that give it life. More and more research is emerging to validate the work of professor and forester Dr. Suzanne Simard that shows trees cooperate with one another rather than compete. The ability for one tree to flourish is directly relative to the overall health of the forest. This observation of the more-than-human world finds its colourful human reflection in Hundertwasser’s window rights.

It is important to clarify that when we say hierarchy, we are not referring to the abstract projections of left and right, but to the way power flows. Power as a spiritual and material substance, not as an abstraction. Power as energy. Life force.

The understandings of hierarchy as something desirable or abhorrent exhibited by theorists on the left and right are abstractions. Failures to understand power on its own terms can lead to it becoming twisted and perverted. Coercion, in effect, is the perversion of power.

For the right, the sought after ideal is a rigid hierarchical model with a fixed top and a fixed bottom, in which every rung of the ladder for the most part is static, with power flowing, if at all, from the top down. For the left, hierarchy is something that needs to be made more level, if not to be abolished entirely.

However, right wing rhetoric is erroneous in believing power on an energetic level can be held at all, that “hierarchical” power dynamics could ever have fixed tops or bottoms, and that points on the continuum are static and immovable.

On the other hand, a common error in the left wing understanding of hierarchy is the unspoken assumption that when we abolish hierarchy, we are abolishing power itself.

Hierarchy is an abstraction, so can be abolished. Power, on the other hand, is real, and power dynamics will not just disappear even if you believe you have abolished them. A reluctance to address this issue unfortunately gives clout to the oft heard right wing critique of the left that “if you try to abolish hierarchy, it will only result in a new one forming in its stead.”

Power dynamics are ever present and power itself cannot be “abolished”, but that does not mean the dynamic has to be oppressive or twisted into one of coercion. It is arguably healthier to calmly and patiently observe the way power flows rather than attempt to pretend—under the guise of “abolishing hierarchy”—that it does not exist. Observing the movements of power is very similar to the way we might chart the flow of sectors (i.e. inputs such as sunlight or water) across our permaculture designs.6 6

Initially, this might be an easier task for witches, magicians, or similar, to engage in as they are used to cultivating an awareness of the power that is flowing all around, whether in sunlight, animals, rocks, trees, or amongst the people sitting around the table at a meeting. However, becoming more aware of power is a pursuit we encourage everyone to cultivate.

Power dynamics are subtle, and they are constantly shifting. Power can never be absolute, static or ossified. The word dynamic itself entails movement. The way power dynamics shift depends less on who you are, and more on where you are, and who you are with.

Imagine you are at a meeting. Are you a guest, or a host? Are you at home or in the street? Or in the field? Are you older or younger than the people present? Are you a different gender? Do you look different from most of those around you? Do you dress different? Are your clothes in as good shape? Is your skin a different colour? Are you proficient in the language being spoken?

Power dynamics can even shift with the subtle inflections caused by body language. Consider who is standing, who is sitting, who arrived late, who arrived early, who sits with their legs spread wide, who fidgets, who waves their arms and hands when they talk, who talks loud and employs excessive pathos, who is calm, quiet, and grounded, who is facing who, and who has their back turned to you.

All of these things, while seemingly small, can create subtle and not so subtle changes in the webs of power that are always present. These observations hold true in the case of any person or group, not just for some people or some groups. This last point is often conveniently forgotten in much of the current discourse of mainstream identity politics.

When we discuss the abolition of hierarchy, the goal should not be to erase power (this, in any case, is physically impossible), but to ensure it flows and in is shared in a harmonious manner, in which health and volition are not stifled, but enabled to flourish.

Furthermore, we would like to clarify that self-defence is not the same as coercion. None would accuse a rose of practicing coercion when someone gets too close and is slashed upon its thorns.

The rose is the true revolutionary, opening toward the light, sovereign, radical, rooted in place—its own blooming, its own existence, its own just doing what a rose does—is a beacon, an instrument for the manifestation of Utopia in the here and now. A conjuring of Utopia void of coercion. The extent of its freedom—of its own volition—defined by the reaches of its thorns.

The magic circle, surrounded by a tangle of thorny roses, is a ring around utopia. A conduit for vision. Our work is not to force these visions upon others but to paint as we please the arms length around the windows of our lives—the window, the portal through which we see the world, and the world sees us—and lead like the rose leads, free, beautiful, recalcitrant— by example of its own bright blossoming: here, now, and ever more.

This essay was first published on July 1, 2021, at Another World.

Slippery Elm

Slippery Elm is the author of The Dead Hermes Epistolary. His poetry and prose in English and Spanish have appeared in dozens of journals and anthologies in both Europe and North America. He has performed as a part of flamenco groups in Europe, Africa, and North America, in courtly settings, as well as in the streets, by hearth corner, and under leaf. He is the editor and translator of the poetry anthology Your Death Full of Flowers and the author of two pocket poetry books. He compliments his poetry and dance by studying Arabic and Hebrew philologies.

For more on this point see Elm, S. “Who’s Afraid of the Lyrical Underground?”, in A Beautiful Resistance 5: After Empire, Gods&Radicals Press: 2021.

For more on this point see Elm, S. The Dead Hermes Epistolary, Gods&Radicals Press: 2019., in which the ecotone in relation to nature, language, and radical politics is a central theme explored throughout.

For more on this point see Elm, S. “Risāla on the East and West”, The Dead Hermes Epistolary, Gods&Radicals Press: 2019.

For more on this point see Elm, S. “Risāla of the Violet Smile”, The Dead Hermes Epistolary, Gods&Radicals Press: 2019.

For more on this point see Elm, S. “Risāla of the Anti-Court”, The Dead Hermes Epistolary, Gods&Radicals Press: 2019.

For more on this point see Elm, S. “Risāla on Agriculture”, The Dead Hermes Epistolary, Gods&Radicals Press: 2019.

lots of great observations here. i've also been very interested in the temporal aspects of utopias. utopian projects must impose control over time as well as space: they depend on a linear understanding of time, in which the present is perpetually catching up with the impossibly good future that they imagine. it's interesting that both sides of the traditional political spectrum (at least here in America, where i am) are driven by misapprehensions about the past: progressives think the past was abhorrent, and try to bury it; conservatives think the past was idyllic, and try to recreate a pure version of it. both imagine that the past—whether good or bad—is gone forever, and incapable of asserting itself on their visions of a future that they control completely.

i've been working on the idea of "phasmatopia" as a counter to this: phasmatopian cultures recognize that the past never stays buried—that the powers of the more-than-human world (which includes our dead and our debts) are always returning to trouble us if we don't show proper respect. the present is an illusion of control that we create and maintain at great cost; phasmatopia is part of a temporal space where the past and the future mingle in unexpected and uncontrollable ways, like the ecotones you beautifully describe here. thanks for this.