This essay is also available as a downloadable PDF. See the end of this post for the download link.

Hear the unstruck sound of the bones within you…

I saw myself

a ring of bone

in the clear stream

of all of it

and vowed,

always to be open to it

that all of it

might flow through

and then heard

“ring of bone” where

ring is what a

bell does

These beautiful lines by Lew Welch have haunted me since 1998. That’s the year I first read them in the Big Sky Mind anthology of Beat poets’ writing on Buddhist themes.1

Artists sometimes create signposts to their afterlife destinations in their works.2 Lew Welch was probably not physically unhealthy; he had great literary gifts and he was appreciated by many friends. Still, he was deeply troubled all his life, and he probably committed suicide in a place where his body could be devoured by vultures in a sky burial — an intention he made explicit in his poetry.

“Then one day in 1971, the hard-drinking Beat poet — an inspiration for one of Jack Kerouac’s characters in Big Sur — walked into the woods of Nevada County, northeast of San Francisco. He took a gun and left behind a suicide note. No body was ever found, which is why biographies end his dates with a question mark. This is also why his friends took to looking at vultures overhead to see if they recognized anything: “Is that you, Lew?”

He was well aware of a second meaning for “ring of bone.” The birds would have picked him up and flown in their circles, eventually dispersing Welch into what he once called “all-that-goes-on-whether-we-look-at-it-or-not.”

These are the final lines of one of Welch’s last poems, “Song of the Turkey Buzzard”:

NOT THE BRONZE CASKET BUT THE BRAZEN WING

SOARING FOREVER ABOVE THEE O PERFECT

O SWEETEST WATER O GLORIOUS

WHEELING

BIRD

I don’t know if Jarod K. Anderson, the poet known as “The Cryptonaturalist,” was inspired by Welch, but there is a powerful resonance between his 2021 poem “Clergy” and Welch’s “I Saw Myself.”

Vultures are holy creatures.

Tending the dead.

Bowing low.

Bared head.

Whispers to cold flesh,

“Your old name is not your king.

I rename you ‘Everything.’”

What a bell does

“Ring is what a bell does” — what a bell does is cause disruption (from the Latin disrumpere "break apart, split, shatter, break to pieces") of mental patterns. This is why bells have long been used to ring out a warning, or to drive “evil spirits” or other unwanted presences or energies away. Bells of all sizes seem to have a similar effect, just on different scales.

Small Bells

Small bells are mentioned as an essential part of a high priest’s clothing in Exodus 28: 31—35.

Moses stipulates how the high priest was to dress when entering the holy of holies—the most sacred space in the Tabernacle and Temple—to make offerings for the sins of God’s people.

The holy of holies was so special and so off-limits to sinners that if the high priest didn’t follow protocol perfectly (a ritual bath, a consecrating sacrifice, and a pure heart) God would strike him dead for profaning the holy place.

But what if that happened? Now you have a dead high priest behind a curtain in a place with no one qualified to recover the corpse. The solution appears to be that the high priest would tie a rope around his waist so his lifeless body could be dragged out. This raises one more logistical question: how would the rope holders know if the man was dead or alive? If they pulled too early they may cause a clumsy mess of the work being done. And the priest wasn’t supposed to interrupt his ritual with an occasional “Still breathing!”

This is where bells come in … The sound of the little bells ringing while the priest moved around was the sound of him being alive, being accepted by God.

If the ringing stopped, it meant God had rejected him and he was dead.

Small bells can also serve to warn predators away, which is why herders often attach them to the necks of domestic animals for the purpose of scaring away predators. Harness bells put on horses or horse-drawn vehicles (“jingle bells”) have been in use since at least 800 BCE. They were always a sign of luck and wealth as well as a means to ward off evil, injury, and illness. (Jingle all the way…)

Bells put on cats’ collars to warn birds serve the opposite purpose: to warn birds that a predator is approaching, and at certain times and places little bells were a required accessory for those who were classified as unclean — like prostitutes — or considered crazy. The bells on their clothing alerted other citizens to their presence, somewhat like the notifications of registered sex offenders today.3

Medium Bells

Handheld bells send more powerful vibrations into the space occupied by the ringer and others who are with them.

It is said that St. Patrick used a handheld bell as a tool for spiritual warfare. A 19th-century book on St. Patrick’s life describes how he used his bell against evil spirits that tormented him:

He rang his bell … “To drive all demons from the upper air.” Then he threw the bell amongst [the evil spirits] in holy anger.

The sides of St. Patrick’s bell shrine — the little metal case — are embellished with openwork panels depicting elongated beasts intertwined with ribbon-bodied snakes. The bell dates to ca. 500 CE, but the shrine was created around the turn of the 11th and 12th centuries, which is close to the time when an English monk named Jocelin of Furness wrote a hagiography that inspired the unsubstantiated yet very persistent legend about St. Patrick driving “serpents” (i.e., Druids or Pagan faiths) out of Ireland. Of course, many contemporary Pagans are by now aware that, like real snakes, this church propaganda has no leg to stand on. Nevertheless, this artifact is thought to have been buried with Patrick, and it is one of Ireland’s best-attested relics.

Handheld bells are a crucial tool used in part of the rite of excommunication, which was performed “by bell, book, and candle” well into the 19th century, and they are still used in Catholic exorcisms to this day.

Gongs

Gongs are usually associated with East Asian cultures, but variations of them were known in ancient Greece, Rome, Egypt, and other civilizations. Their uses are similar to those of bells: they disrupt patterns of thought in order to refocus attention. Sometimes, striking a gong4 signals a crucial moment during a ritual or ceremony: the powerful vibration dispels distractions and pulls people into the full significance of what they are experiencing. Today, music therapists claim that “gong baths” can help resolve emotional, spiritual, psychological, and physical dissonance, opening doors and windows between the soul and the Universe. At the very least, listening to them is relaxing: their sound does have a way of dissolving ordinary thoughts and preoccupations, which can seem “demonic” when our inner voices are cruel or obsessive.

Pots and pans

Sometimes, people who lack access to medium-sized bells or gongs strike pots and pans. However, the purpose is unlikely to be ceremonial or meditative: they are used in acts of banishing or protest in order to affect someone or something unwelcome. Ovid stated that people used to beat bronze vessels during an eclipse and at the death of a friend to scare away demons. Even in our time, Wikihow, a site noted for its practical advice on how to do just about anything, also recommends banging on pots and pans to get rid of demons.

Similar procedures are followed on New Year’s Eve: church bells are rung at midnight5 and pots and pans are beaten to drive bad spirits away and keep the start of the new year free of old hauntings. There is even an echo of this in the custom of tying tin cans to the back of newlyweds’ getaway cars.

At the community level, there is a long history of protesting unjust marriages or governments by banging pots and pans. It can be observed at protests worldwide, and even the most recent round of French protests this year featured a cacophany of kitchenware, much to the consternation of President Macron.

Large Bells

While smaller bells are believed to affect the close surroundings of those ringing them, for centuries it has been believed that large ones also had the power to affect weather.6

Bells were first installed in churches during the Dark Ages. Prior to that, other methods used to call worshipers to services included playing trumpets, striking wood, shouting, or sending a courier around. Their use was officially sanctioned by Pope Sabinian in 604 CE, which is about the same time that Greek monasteries replaced trumpets with planks or flat metal plates (called semantron) which are struck to summon monastics to worship.7

However, bringing people together to worship, or to signal important events such as the end of a war, emergencies such as a fire, or to announce deaths, or spiritually assist women with childbirth8 were not their only purposes.

William Durandus (aka “Doctor Speculator”) discusses various purposes for church bells in his Rationale Divinorum Officiorum, a treatise on the origins and meaning of ecclesiastical practices, and on elements of church architecture.

The reason for consecrating and ringing bells is this: that by their sound the faithful may be mutually cheered on towards their reward … that the hostile legions and all the snares of the Enemy may be repulsed; that the rattling hail, the whirlwinds, and the violence of tempests and lightning may be restrained; the deadly thunder and blasts of wind held off; the spirits of the storm and the powers of the air overthrown; and that such as hear them may flee for refuge to the bosom of our holy Mother the Church ... (etc.)

At Roman Ritual consecrations (sometimes called “baptisms”) of church bells, the bells are anointed with holy water, holy oils, and blessed salt and the priest prays:

“ … Grant, we pray, that this bell, destined for your holy Church, may be hallowed by the Holy Spirit through our lowly ministry, so that when it is tolled and rung the faithful may be invited to the house of God and to the everlasting recompense. Let the people’s faith and piety wax stronger whenever they hear its melodious peals. At its sound let all evil spirits be driven afar; let thunder and lightning, hail and storm be banished; let the power of your hand put down the evil powers of the air, causing them to tremble at the sound of this bell, and to flee at the sight of the holy cross engraved thereon.”

Liturgical and literary sources too numerous to cite all agree that properly consecrated church bells possessed all these powers and more, including the ability to banish epidemics.9

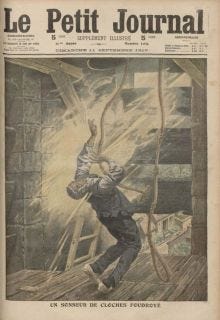

Yet, despite the intention to ward off storms and other harmful influences, it was a widely-acknowledged fact that lightning very often struck church towers and killed bell-ringers. One of the worst incidents was described in A Book About Bells, where the Rev. George Tyack notes that in one violent storm “lightning struck no less than twenty-four churches, despite their defensive bell-ringing, whilst churches who did not sound their bells emerged from the storm unscathed.” So many people died while ringing church bells during storms that the practice was banned in various local edicts, and it was outlawed by the Parlement of Paris in 1787. However, many authorities were reluctant to enforce this unpopular enactment and bell-ringing considered to be a very hazardous profession.10

Benjamin Franklin’s lightning rods offered relief to building towers and bell ringers from deadly strikes, but the habit of ringing bells for protection from storms still persisted. As late as 1824, four new bells were baptized against lightning and installed at the Cathedral of Versailles, and at Dawlish in Devon (southwestern England) bells were still being rung against storms in 1899. Even today, some Europeans are still ringing church bells in an attempt to dispel or turn storms.

A “love thy neighbor” ethic was sometimes conspicuously absent in the practice: Luc Rombouts claims in Singing Bronze: A History of Carillon Music that residents of neighboring towns would sometimes use their bells in an attempt to force thunderstorms to shift over to the other village.

More efforts at controlling the weather

The belief that bells could turn storms away was transformed in the Enlightenment, when leading philosophers such as René Descartes and Francis Bacon, agreed that ringing bells was a valid method, though they disagreed with the churchmen on how it worked. According to Philip Dray in Stealing God’s Thunder, Enlightenment scientists thought the acoustical disturbance of ringing a large bell created “some concussive energy that deterred lightning bursts.”

This theory, and others like it, was disproven, but it wasn’t too long before more technologies were introduced that aimed control the weather using similarly aggressive methods. For example, at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries there was a fad for using specially-shaped cannons to ward off hail by blasting shock waves at the clouds.11 They are still in use today in some places, particularly vineyards.

Conversely, other efforts at controlling the weather involved attempting to blast clouds open either where rain was wanted or on enemies. The observation that rain often follows a battle had been made by Plutarch, and Napoleon often tried to induce rain by firing artillery at the ungenerous sky. Similar experiments were repeated in Texas, using dynamite-laden balloons. During the Cold War, a “weather race” developed between the two superpowers, who believed that controlling storms was key to world domination.

Siouxsie and the Banshees sing about the practice of using cannons to force clouds open in their haunting song “Cannons,” one of my top favorite pieces by one of my all-time favorite artists, which I hope you will listen to right now.

“Cannons”

Troubled weather's on its way

Tempests threaten us today

There's no respite from long dark nights

Just the fantasy of spring

From the hailstones of summer

To a scorching winter land

A frozen death sleep, then this heat

Beats down on this buckled land

Flames lick closer to the core

From city limits fireball

And in a headless chicken run

Race red and screaming fire engines

Then the cannons came

Oh 'neath the brooding sky

Beneath its baleful eye

The cannon shot, the cannon crack

Disturbing night dreams

People fled in droves

To the lakes and to the shores

Left behind a near ghost town

Save the life of the cannons resounding

Still there was no rain

No rain, no rain, no rain

Once more in the line of fire

Hovers the preying sky

The cannons aim jabs at the eye

Heralding the rain

Heralding the rain

Oh, heralding the rain

Heralding the rain

The imagery she uses to capture a dysfunctional landscape and climate was probably inspired by T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, which is rife with descriptions of desiccated, failing landscapes; “dry sterile thunder without rain” is specifically mentioned.12

European land spirits in folktales

In the visions shared by Siouxsie and Eliot, it is notable that no other entities besides human beings seem to occupy the wastelands. However, this is an interesting omission. Were the lands cursed because the spirits had abandoned them? Or did the spirits abandon them because they were cursed by people? What would have caused the beings that inhabited wild places to abandon their patronage of water and wild lands?

The places inaccessible to men are inhabited by a host of very ancient creatures who haunt woods, glades, and groves, and lakes and springs, and brooks; whose names are Pans, Fauns, Fontes, Satyrs, Sylvans, Nymphs, Fatui or Fantuae [fairies], or even Fanae.13

During and after the Christianization process, churchmen kept themselves busy for many centuries trying to suppress the “worship” or belief in land spirits by members of their flocks. Converts chopped down sacred groves and destroyed the temples, shrines, and mounds associated with the old cults. However, stamping out belief in land spirits was more difficult than suppressing the belief in Pagan high gods because, as Lecouteaux points out, these “numinous forces” were “closer to man, and therefore held a greater significance for their daily life,” and because their cults were associated with hearths and fields rather than with public facilities.

Demonizing them proved easier then convincing people that they did not exist. In many cases, they were demoted to “small gods,” a modern category that includes a variety of beings mostly known now from folklore and fairy tales. Those interested in the topic might want to follow up their reading of Lecouteaux with this excellent anthology titled Fairies, Demons, and Nature Spirits: "Small Gods" at the Margins of Christendom published by Palgrave.

Those who prefer primary sources instead of scholarly reflections can find numinous beings both large and small in the recently rediscovered folktales that were collected by Franz Xaver von Schönwerth (1810-1886). Schönwerth was a folklorist who took inspiration from the Grimm brothers, and he recorded legends, fairy tales, nursery rhymes, proverbs, and other forms of oral culture. Using methods that became exemplary for other researchers, he observed and described the everyday life of peasants, laborers and servants in the Upper Palatinate region. Schönwerth was so highly regarded by the Grimms that they told the king that he was the only person who had their blessing to continue their work after their deaths.

Sadly, however, Schönwerth’s reputation faded because only one volume of his work had survived; that is, until 2009, when Erika Eichenseer, a scholar of regional folklore, discovered a trove of his unpublished material, including some 500 folktales, in a dusty box in the municipal archive in Regensburg. An English edition of 72 of the tales was published under the title The Turnip Princess by Penguin in 2015.14

The stories collected in The Turnip Princess deserve to be read, re-read and the mysterious wood sprites, mermaids and mermen, and more powerful entities such as the Lady of the Woods, who showers rewards upon those who “remain faithful to customs from times past” pondered upon, for their mysteries are manifold.

Church bells and the (temporary) eviction of land spirits

In his essential masterwork Demons and Spirits of the Land, the French medievalist and philologist Claude Lecouteaux uses the term “land spirit” as an equivalent to the Latin genius loci (place spirit). In this work, the “places” he means are those that have not been built upon or cultivated for crops. These spirits can be a numen or daimon “attached to a specific place that it owns and protects against any incursion” (p. 3). If it has been nicely propitiated, a person building something in its territory may end up with a helpful household spirit; if not, they may experience various kinds of trouble and find it impossible to erect buildings.

There is a very clear-cut opposition between civilized space — cities, towns, castles, villages, and cultivated lands — and wild spaces like moors, forests, mountain, marshes, and the sea … the natural refuges for our unknown or poorly known neighbors (pp. 13, 102). Those who would take possession of a piece of land must come to terms with its numinous powers, defeat them, or concede the land to them.

Both Schönwerth and the Grimms provide many instances of the use of Christian rites and practices, such as baptism, holy orders, etc. to thwart evil intentions land spirits had toward individuals. Sometimes these means are effective and sometimes they aren’t (in the stories), but the church had a broader solution that could protect entire communities: bells.

The holy water, holy oils, and blessed salt and spoken prayers used to consecrate church bells were all supposed to have the virtue of repelling Satan, demons, and diseases, but they could not feasibly be physically dispersed to a wide enough area. However, the ringing of a bell could “cleanse” an area of several square miles.

Fairies (to be understood here as land spirits, in all their diversity) have often been said to have an intense dislike of church bells. For instance, in her article “The English Fairies,” the fairy folklorist K.M. Briggs mentions a Worcestershire fairy who had to leave her home because of the church bells, complaining “so bitterly”:

I can neither sleep nor lie,

Inkberrow's ting-tang hangs so high.

Sometimes, land spirits would attempt to prevent the construction of churches so that bells wouldn’t be installed in their territory. However, once the buildings were up and the bells were ringing, they were exiled to wilder places — until such time as people abandoned them.

Fairy Bells

Of course, the Good People had their own bells, which were tiny and usually only selected people could hear them. Like the small bells used by other faiths, fairy bells signaled a rupture in the weave of reality and a need to focus on what is transpiring. For instance, the approach of Thomas the Rhymer’s Fairy Queen was heralded by the bells woven into her horse’s mane. And the Green Children of Woolpit, who were understood by people at the time to have been fairy children, told of being guided by bells into the human world — which indicates the portal could open either way.

Sometimes, a righteous person might even be given their own bell to ring, as in the Portuguese folk tale "Silver Bells." Like the Grimms’ “The Singing Bone,” which I discuss below, this story tells of a little girl whose fairy aunt gave her a bell necklace that the girl’s wicked mother could not remove. She uses it to befriend a wolf and a fox, which affords the interpretation that she had an understanding of ecological balance (i.e.: that the predators are necessary and should not be considered in the same category as monsters that are sent by God to punish human sins) that was superior to the ideas of wicked and foolish people. I propose this interpretation because Mirabella sacrifices herself (escapes to the realm of the dead) when her mother threatened to order the killing of all the wolves in the realm.15

It is almost certain that the old Irish craebh ciuil, which was a branch that suspended a number of tiny bells and produced a sweet tinkling when shaken, is an echo of the legendary “Silver Bough” (An Craobh Airgid)16, which may have been a shamanic instrument or magical wand. Some examples have been recovered by archaeologists, and contemporary Bards and Druids use them in ritual and music.

Singing bones in folktales

In the Grimms’ tale “The Singing Bone,” a wicked older brother killed his younger brother in order to claim the prize offered for slaying a wild boar. However, he is brought to justice by the victim’s oracular singing bone:

… the elder brother let the other go first; and when he was half-way across he gave him such a blow from behind that he fell down dead. He buried him beneath the bridge, took the boar, and carried it to the King, pretending that he had killed it; whereupon he obtained the King's daughter in marriage. And when his younger brother did not come back he said, "The boar must have killed him," and every one believed it.

But as nothing remains hidden from God, so this black deed also was to come to light. Years afterwards a shepherd was driving his herd across the bridge, and saw lying in the sand beneath, a snow-white little bone. He thought that it would make a good mouth-piece, so he clambered down, picked it up, and cut out of it a mouth-piece for his horn. But when he blew through it for the first time, to his great astonishment, the bone began of its own accord to sing:

"Ah, friend,

Thou blowest upon my bone!

Long have I lain beside the water;

My brother slew me for the boar,

And took for his wife

The King's young daughter."

Needless to say, the evildoer is punished.

In my interpretation, outside of the human drama of justice and injustice there a story being told about people’s relationship to the land. Wild elements were out of balance, as we see at the beginning of the story when the boar is laying waste to fields and cattle, and even killing people. When the brother who had truly killed is revealed, the victim’s reward is to buried in the earth in a more fitting way, while his deceitful brother is thrown into the water in a dishonorable way, exactly as he deserved.17

In Schönwerth’s tale “The Snake Sister” (pp. 94—97) an orphan named Annie is sent by her witch stepmother to a well guarded by wild animals. She answered a dwarf’s question honestly, and was given a crust of bread to throw to the beasts, which established trust and friendship between them. After Annie drew water from the well, she heard a voice, and then another and another asking her to scrub them. The voices were coming from three skulls, which she washed clean with her well water. The skulls then blessed her with beauty, success, and the fate of becoming a queen, “even if it means that you are first turned into a snake!” Annie’s stepsister was sent to the well, where she failed to help the skulls, and she was cursed with the inverse of Annie’s blessings. The stepmother’s treachery resulted in Annie being turned into a water snake, but she was able to rescue her true brother, and — after a period in which she was buried under a new castle’s threshold, like the ancient sacrifices — she was restored to life and married the king.

From the king marrying a woman associated with the sacred forces of the land to the oracular skulls and the “right relationship” Annie establishes with the land spirit (dwarf) and wild animals, a great antiquity shines through many of the elements in this tale.

Singing bones in the archaeological record

Some of the motifs preserved in these stories may be ancient that they even predate our species: you can listen to haunting melodies made using a replica of a 50,000-year-old Neanderthal flute on this page. There are also bone flutes made by Homo sapiens that have been dated by archaeologists to the Paleolithic period. They were carved from the bones of cave bears, mammoth, and large birds (griffon vulture and swan) — but also from people, a habit which persisted for many millennia.

The use of human remains for musical instruments seems morbid by today’s standards, but it was not so unusual in the past. Bronze age Britons often remembered their dead by holding onto parts of their bodies as relics, sometimes using them as ritual objects, ornaments, or musical (or oracular) instruments. Often, the relics were kept for decades after the person died, and perhaps the survivors took comfort in hearing them sing again in the melodies musicians coaxed out of the instruments, or in voices they perceived as emanating from the bones.

“It’s indicative of a broader mindset where the line between the living and the dead was more blurred than it is today,” [Thomas Booth, a researcher from the University of Bristol] said. “There wasn’t a mindset that human remains go in the ground and you forget about them. They were always present among the living.” … “Our study indicates that bronze age people were accustomed to handling the bones of the dead, even in their day-to-day lives,” said Bruck … Radiocarbon-dating of curated bones suggests that bronze age people’s sense of identity and belonging was based on their links to known kin who had died in the past few decades rather than to distant and anonymous ancestors.”

Oracular bones and birds

As I describe in my book, The White Deer, oracular truth telling and even singing heads had been well known in the Greek and Roman worlds (such as Orpheus’ head, which had been torn off his body by maenads but continued to sing), and in Norse legends (the oracular severed head of Mímir). The head of Brân the Blessed, who was a giant and a king in Welsh mythology, was cut off at his request after he received a fatal wound in his foot. In accordance with his further instructions, it was then taken to the White Hill of London, which may be the site where the Tower of London now stands. We also find sentient severed heads or skulls in Russian fairy tales, such as the skulls with shining eyes on Baba Yaga’s fence. Most of the magical talking heads found in Celtic romances had not been taken from warriors killed in battle, but from kings or chieftains who were slain in unusual and highly symbolic ways. These were deaths that (like those of the Christian martyred saints) set them aside from other mortals, and, because they were specially blessed, the heads continued to facilitate healing. I drew inspiration from John Grigsby’s Warriors of the Wasteland, which describes the myths and cults associated with oracular heads in a great deal of detail.18

Birds, as I mentioned above, are also often associated with fae (“fairy,” but also “fateful”) powers and with oracular revelations. In the Grimms’ story titled "The Almond Tree" or "The Juniper Tree" it is a bird that reveals the murder of a little boy by his stepmother.

The victim’s younger sister, who was falsely blamed for the murder, dutifully gathers up his bones (after her mother cooked and served his flesh to her husband). Then she buries them beneath the juniper tree with a handkerchief. Suddenly, a mist emerges from the juniper tree and a beautiful bird flies out. The bird visits the local townspeople and sings about its brutal murder by the stepmother so that everyone can hear his voice:

''It was my mother who murdered me;

It was my father who ate of me;

It was my sister Marjory

Who all my bones in pieces found;

hem in a handkerchief she bound,

And laid them under the almond tree.

Kywitt, kywitt, kywitt, I cry,

Oh what a beautiful bird am I!"

The motif of talking and truth-telling birds is ancient indeed: the study of avian oracles had been systematized in Mesopotamia and passed on to the Hurrians and Hittites, Greeks, Romans, etc. In Aristophanes' play The Birds (716—24), the chorus of birds claims a lineage older and more legitimate than that of the Olympian gods, and they explain the benefits they bestow on humans, especially in the role of oracular consultants. This is rather unsurprising, given that that ancient Greek word for bird οἰωνός [oiōnós] has all three meanings of “large bird,” “bird of prey,” and “omen, token, or presage.”

We are your oracles—your Ammon, Delphi, Dodona, and your Apollo. You don’t start on anything without first consulting the birds, whether it’s about business affairs, making a living, or getting married. Every prophecy that involves a decision you classify as a bird. To you, a significant remark is a bird; you call a sneeze a bird, a chance meeting is a bird, a sound, a servant, or a donkey—all birds. So clearly, we are your gods of prophecy.

Here, the oracle is delivered via both birds and bones,19 which brings us full circle to the themes laid out in the beginning of this article.

The unstruck sound of bliss

It is said that the sound of universal harmony is eternal and “unstruck.” Some identify it as Anahata Nada, or Om, while a Renaissance tradition theorized about a “music of the spheres.” I’m not partial to either conceptions, which — in my view — are either too rarified or, sometimes, overloaded with symbolism. Nor do I favor the Christian idea of God’s world-forming Logos, which implies an uncreated creator deity.

Each thing is related to all the others: “Everything points to something not itself. This would be a good first definition of ecology. The skilled outdoorsman, hunter, or scientist watches and listens to the birds, since their calls, or their silence, disclose the presence of other animals … Even no voice at all gives powerful counsel.”20

Terri Windling quotes Terry Tempest Williams in her gorgeous blog article on the foklore of birds. In Refuge, Williams writes that she loves birds: "because they remind me of what I love rather than what I fear. And at the end of my prayers, they teach me how to listen.”

Not much teaching is necessary: simply listen closely to the birds, feel the wind in the trees, taste the approaching storm. Hear the unstruck sound of the bones within you; they’re already vibrating with “all-that-goes-on-whether-we-look-at-it-or-not.” All of this becomes becomes clearer when we tune out the chatter and nonsense, and then we become able to read the signs and omens. As the saying goes, the things we know most fully, we “know in our bones.”

May your bones ring true.

Melinda Reidinger

Melinda Reidinger lives in a rural part of the Czech Republic with her family and two wolfdogs. She's a former academic, and now a writer and translator, and her personal practice is best described as eclectic hedgewitchery with elements of classical and fayerie cults. She is also the author of The White Deer: Ecospirituality & The Mythic.

Download this article as a PDF.

This book and a Lonely Planet guide were the only volumes I carried with me during a 6-week solo overland journey across China and into Tibet. “I Saw Myself” is also published in Ring of Bone: Collected Poems of Lew Welch (2012).

As I discuss in my article “The White Deer As Memento Mori,” the painter John William Waterhouse created both a guide and a destination for himself in two unfinished paintings he was working on when he knew he was dying of cancer.

In the same way, “when storytellers dissolve into their tale … Not just any storyteller, of course, but the ‘righteous man’ dissolving into the story of his life, which, it turns out is a story in which non-human beings and inanimate substances come alive” they perform a powerful act of enchanting the world. See Michael Taussig, The Corn Wolf, Chapter 3, especially p. 25.

The character of Essel, who is a sex worker, wears compulsory bells in David Lowery’s magnificent film The Green Knight (2021), which is a haunting, evocative take on the legend of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

The song "Get It On / Bang A Gong"— originally by T. Rex, but perhaps better known in the rendition by The Power Station, a Duran Duran spinoff band — refers to altering one’s consciousness in an entirely different way. The phrase originated in opium dens in the second half of the 19th century: sounding the gong was the way to ask for service.

T. Rex would have been referring to it in the same way as Cab Calloway’s song “Minnie the Moocher,” in which the titular character takes up with a “cokie” called Smokey, who “took her down to Chinatown and showed her / how to kick the gong around.” Between verses, Calloway mimicked the actions of snorting cocaine and shooting heroin, which indicates that in the 1930s banging or kicking the gong had become slang for any illegal drug use.

This tradition of using church bells for cleansing and moral renewal for the entire land at the cusp of the new year is captured in the lines “ring out the old, ring in the new,” by Alfred, Lord Tennyson in his famous poem “Ring Out, Wild Bells.”

This tradition of using church bells for cleansing and moral renewal for the entire land at the cusp of the new year is captured in the lines “ring out the old, ring in the new,” by Alfred, Lord Tennyson in his famous poem “Ring Out, Wild Bells.”

The word “bellwether,” incidentally, doesn’t have anything to do with the weather. Rather, it refers to the lead sheep in a flock (a wether is a castrated ram) who wears a bell. The tinkling of his bell indicates to the shepherd which direction the animals are moving. Figuratively, it’s any indicator of how a situation is likely to change or develop. Perhaps, the false meaning actually “rings” true, though, if we consider the “bellwether” of church bells being used to attempt to control storms as an indication of the scientific trends that were to follow.

Eastern Orthodox churches adopted the use of semantra because the Ottoman laws banned the ringing of bells.

(For a fee, of course.) Additionally, according to Melanie Warren writing for Folklore Thursday, “the Church’s belief that the Devil feared the sound of bells became extended by the people to include all evil spirits, so that the tolling of the ‘passing bell’ served two purposes; to announce the death of a person and invite prayers, and secondly to frighten away spirits who might be lying in wait for the newly-departed soul. The greater the fee paid, the louder the bells, so that the spirits might be driven farther away. In Lancashire, once the burial was over, a merry peal would be rung in order to encourage angels and discourage evil spirits – this custom was in practice well into the 19th century.”

What’s old is new: it seems that bells were also deployed during the covid years. I have not yet been able to access the article Illness, Metaphor, and Bells Campanology under COVID-19, but if I obtain a copy I’ll update this note with a comment on it.

Okay, okay, “dead ringer” doesn’t really refer to one of these unfortunates, nor does it come from fakelore about people buried alive and ringing little bells to request disinterment. (There are no documented cases of living people being successfully excavated from safety coffins.). Rather, the phrase comes from horse racing fraud, and I simply couldn’t resist the pun.

One relatively modern theory advanced for rainmaking called for setting large tracts of forest in the Appalachian Mountains on fire every Sunday. More recently developed technologies include cloud seeding, Chinese rain rockets, lasers, and electrical "zappers." Now, Bill Gates wants to fund programs for Solar Radiation Management, a form of geoengineering in which microparticles are dispersed into the upper atmosphere in an attempt to deflect sunshine in order to mimic the sun-blocking effect of massive volcanic eruptions. What could possibly go wrong?

Belief in technological “salvation” belongs with the other salvation myths, and even many scientific experts and representatives of Indigenous groups are petitioning for a halt to further experimentation.

Siouxsie wrote: "I saw a documentary about this period of freak weather in the '20s, when it was either incredibly hot or ridiculously cold. TS Eliot had written a poem about it. Apparently, in desperation, the locals would fire a cannon into this oppressive sky each night in the hope of bursting a rain cloud. The image of this deserted town, with someone having to stay behind to fire the cannon, stuck with me and became ‘Cannons’ on the new album."

Martianus Capella (5th c.) is quoted by Claude Lecouteaux on p. 25.

The discovery of the lost tales caused an immediate stir in the communities of those who study and love fairy and folk tales, and the tales themselves caused a great deal of rethinking of “typical” or “classic” motifs known from the Grimms’ or Perrault’s tales. “Cinderfellas” in the stories Schönwerth collected from his informants are just as likely to be hapless and in need of help as Cinderellas, and he preserved the rough, raw quality that some of his colleagues edited out in conformity with the literary tastes or social mores of their time. See the Harvard folklorist Maria Tatar’s excellent introduction to The Turnip Princess, especially pp. xiii—xiv. Most of the stories that portray land spirits are in the section called “Otherworldly Creatures.”

“Fiends” that cast fires down onto the earth (lightning?) and cause earthquakes and “clamors by night” in order to destroy the king’s palace and prevent the construction of a church at Vienne were described by Jacobus de Voraigne in his Golden Legend. The fiends also possessed wolves, which ran amok around the city devouring old people and children. There are so many cases of “demonic” forces attempting to prevent the construction of churches described in hagiographies that an entire book could probably written. Voraigne was also a big believer in the virtues of bells, writing elsewhere “ … the evil spirits that be in the region of the air doubt much when they hear the bells ringing; thus the bells are rung when it thunders, or when great tempest and outrages of weather happen; to the end that the fiends and wicked spirits should be abashed and flee, and cease of the moving of tempests."

For more on the “silver branch,” see W. Y. Evans-Wentz’s The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries (p. 336). “To enter the Otherworld before the appointed hour marked by death, a passport was often necessary, and this was usually a silver branch of the sacred apple-tree bearing blossoms, or fruit, which the queen of the Land of the Ever-Living and Ever-Young gives to those mortals whom she wishes for as companions … Often the apple-branch produces music so soothing that mortals who hear it forget all troubles and even cease to grieve for those whom the fairy women take.”

Parallel tales can be found in numerous murder ballads where there are two sisters instead of two brothers; most of them preserve the haunted musical instrument, but it’s usually a harp or fiddle strung with long golden hairs, and sometimes the younger sister comes back to life.

Unfortunately, the work is currently out of print, but it is possible to buy it from online used bookstores, or you can see some of his work here.

In Lee Morgan’s Sounds of Infinity, a survey of fairy lore, he claims that European fairy lore often features beings who can shapeshift into birds or which possess bird feet or wings (p. 52).

Dale Pendell, The Language of Birds, p. 10.

Thanks for your incredibly rich essay Melinda....and I do miss hearing the old church bells for some reason.....On another note your discussion of honoring sculls remind me of something I have just read.I recently told me daughter, Greeks really know how to do funerals! This was based on all the lavishly dressed funeral attendees I’ve encountered in Montreal Orthodox services. Her father/my husband’s family is from Southern Greece, from Laconia. Recently I found some research on Greek funerals in that area, in particular in Mani. The culture has been characterized as militaristic and patriarchal. (There were many pirates from this area during the Turkish occupation.) Young girls until recently were sold for their doweries and spent much of their life slaving in home and field. Elderly women thought reigned supreme at funerals. It was almost as if it was their chance to show power-driven, materialistic, macho men where we all end up.

These old black clad women were more powerful than the village priest and up until the mid-20th century, they were the ones who, after 3 years had passed, dug up the corpse in the coffin, de-fleshed it, and purified the bones with a solution of vinegar and herbs. This was called “The Opening,” and people came from miles around to pay their respects and feast. And although I couldn’t find much about this additional practice, these elderly funeral priestesses used the vinegar purified bones in oracular ways. The bones were then prepared for re-burial, and the village priest did his small Christian part…..For what I read, not doing ‘The Opening” meant disrespecting the dead and abandoning them to rot away.

Apparently Southern Greece was late to be Christianized as were parts of Eastern Europe and into Russia. So these old way continued for a very long time.